The global AIDS response is under threat

Introduction

Take a look at some of the most pressing issues affecting the AIDS epidemic to date.

SCROLL DOWN

Over the past two and a half years, the colliding AIDS and COVID-19 pandemics—along with economic and humanitarian crises—have placed the global HIV response under increasing threat.

In some parts of the world and for some communities, the response to the AIDS pandemic has shown remarkable resilience in adverse times, which has helped avoid the worst outcomes. However, global progress against HIV is slowing rather than accelerating: the latest data collected by UNAIDS show that while new HIV infections fell globally last year, the drop was only 3.6% compared to 2020—the smallest annual reduction since 2016.

Eastern Europe and central Asia, Middle East and North Africa and Latin America have all seen increases in annual HIV infections over the past decade. In Asia and the Pacific, UNAIDS data now show that new HIV infections are rising where they had been falling over the past 10 years.

Every day, 4000 people—including 1100 young people (aged 15 to 24 years)—become infected with HIV. If current trends continue, 1.2 million people will be newly infected with HIV in 2025—three times more than the 2025 target of 370 000 new infections.

The human impact of the stalling progress on HIV is chilling. In 2021, 650 000 people died of AIDS-related causes—one every minute. With the availability of cutting-edge antiretroviral medicines and effective tools to properly prevent, detect and treat opportunistic infections such as cryptococcal meningitis and tuberculosis, these are preventable deaths. Without accelerated action to prevent people from reaching advanced HIV disease, AIDS-related deaths will remain a leading cause of death in many countries.

Trends in HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths are driven by the availability of HIV services. Here, too, signs are worrying as expansion of HIV testing and treatment services stalls. The number of people on HIV treatment increased by only 1.47 million in 2021 compared to net increases of more than 2 million people in previous years. This represents the smallest increase since 2009.

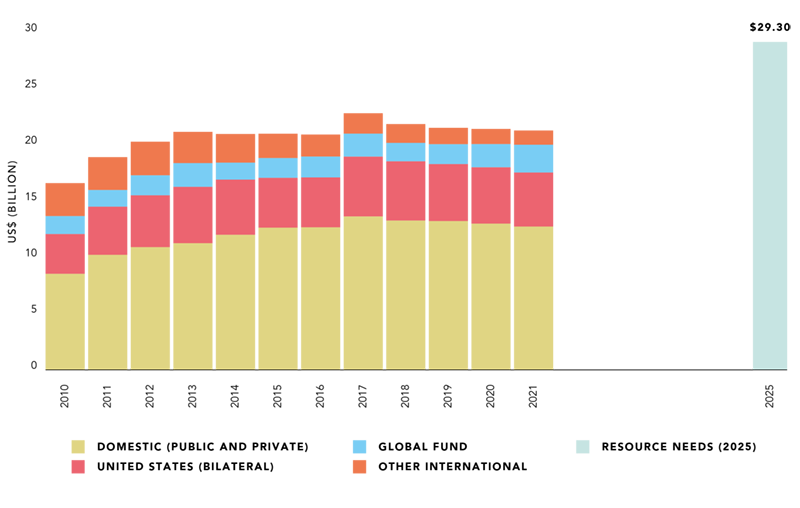

Progress is slowing as resources available for HIV in low- and middle-income countries decline, leaving their HIV responses US$ 8 billion short of the amount needed by 2025.

Official development assistance for HIV from bilateral donors other than the United States of America has plummeted by 57% over the last decade. In 2021, international resources available for HIV were 6% lower than in 2010.

Unlike previous years, however, domestic HIV investments are not replacing lost international funding. Instead, domestic funding in low- and middle-income countries has fallen for two consecutive years, including by 2% in 2021. Global economic conditions and the vulnerabilities of developing countries—which are exacerbated by growing inequalities in access to vaccines and health financing—threaten both the continued resilience of HIV responses and their ability to close HIV-related inequalities. The World Bank projects that 52 countries, home to 43% of people living with HIV, will experience a significant drop in their public spending capacity through 2026.

High levels of indebtedness are further undermining the capacity of governments to increase HIV investments. Debt servicing for the world’s poorest countries has reached 171% of all spending on health care, education and social protection combined. Increasingly, paying off the national debt is crowding out health and human capital investments that are essential to ending AIDS.

New investments are needed now to end AIDS by 2030. Making good on the promises made within the United Nations General Assembly in 2021 will be markedly less expensive than underinvesting now and risking further backsliding. Over the last year, indifference has slid towards neglect, and this lack of solidarity is both morally wrong and harmful to all countries.

The most vulnerable and marginalized are being hit the hardest.

People with less social power and fewer protections under the law are often at higher risk of HIV infection. Adolescent girls and young women (aged 15 to 24 years)—one of whom becomes infected with HIV every three minutes—are three times more likely to acquire HIV as adolescent boys and young men of the same age group in sub-Saharan Africa.

Children comprised 4% of people living with HIV in 2021 but 15% of AIDS-related deaths, and the gap in HIV treatment coverage between children and adults is increasing rather than narrowing.

Key populations account for less than 5% of the global population, but they and their sexual partners comprised 70% of new HIV infections in 2021. In every region of the world, there are key populations who are particularly vulnerable to HIV infection.

Racial and ethnic minorities often experience substantial HIV-related inequalities, such as in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the United States, where declines in new HIV diagnoses have been smaller among Black people than among white populations. In Australia, Canada and the United States, HIV acquisition rates are higher in indigenous communities than in non-indigenous communities.

Among the deeply concerning broader trends of the global AIDS response, there is some good news to report. National responses that were adequately resourced, adopted sound policies, and made prevention and treatment technologies widely available have demonstrated remarkable resilience and impact. Countries as diverse as Italy, Lesotho, Viet Nam and Zimbabwe cut new HIV infections by more than 45% between 2015 and 2021.

The Global AIDS Strategy 2021–2026 provides a clear, evidence-informed blueprint for getting the AIDS response on track. The world’s governments have pledged to take concrete steps to translate this blueprint into action. No miraculous “silver bullet” is needed: using the tools already at its disposal, the global community simply needs to translate its commitments into concrete results for people.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine are generational challenges, and their negative impacts are far-reaching. Along with the bad, however, comes some good: these crises have also demonstrated the world’s ability to mobilize massive resources and shift policies quickly in the face of extraordinary adversity. The innovation and leadership galvanized by the COVID-19 experience also underscore the pivotal role that communities can play in preserving service access and reaching the most vulnerable and marginalized people.

Greater political courage is needed to end HIV-related inequalities and revive and further strengthen global solidarity around this goal.

We know what needs to be done to end AIDS, and we have the tools we need. Now our challenge is to summon the courage required to close gaps in the response and end HIV-related inequalities.

In this chapter, read more about the existing challenges and the tools available to close the gaps in the AIDS response and end HIV-related inequalities.